Table of contents

Open Table of contents

Introduction

Preface

Speech is a fundamental means of communication in society, used to convey understanding, share information, give instructions, and interact within groups. However, challenges arise when humans need to interact directly with computers. Recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and speech-to-text technology have significantly facilitated the interpretation of human speech, reducing the reliance on digital electronic peripherals such as keyboards, mice, and remote controls for providing instructions to computers. AI is evolving rapidly, profoundly impacting human life with its computing power and precision. It has become central to our daily interactions, particularly through voice assistants like Siri, Cortana or Bixby, which are automatically linked to phones. These assistants have propelled the evolution of voice recognition, helping us complete administrative tasks effortlessly.

As AI continues to advance and permeate various aspects of our existence, it opens up new, unexplored horizons in industry, potentially benefiting those who may not fully enjoy certain products of our society. This could mark a turning point within the videogame industry, targeting new audiences through automatic voice recognition technology.

Objective

This Bachelor’s thesis aims to explore voice control within the videogame medium, investigating the extent to which voice, compared to traditional digital peripherals, can succeed in opening up a new genre within the industry for both able-bodied and disabled players. It also seeks to understand how the complexity of language can affect videogame mechanics.

The thesis begins by introducing fundamental concepts to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the work involved and the complex aspects to be addressed. It briefly examines the evolution of automatic speech recognition (ASR), its societal impact, and its various applications. The goal is to understand the basics while focusing on the multifaceted uses of ASR in industry, particularly its application in videogames. The aim is also to shed light on the concepts of voice control at various levels of detail for controlling game mechanics and gameplay across multiple genres.

Building on various projects which have contributed to this community of practice, this thesis develops a protocol for testing mini-games to analyze player responsiveness and adaptability in diverse environments. These tests aim to gather data on the use of voice and conventional peripherals, with the intention of synthesizing a response on the possible future use of ASR within the videogame industry, its impact on players, and the hypothetical controls to be explored to enhance the field of speech within an interactive medium.

Thesis Overview

This thesis is structured into three main sections, each serving a distinct purpose in exploring voice recognition control in the videogame industry. The first section introduces key concepts essential for readers to understand the object of this study. It lays the groundwork for comprehending the practical results and drawing informed conclusions from the thesis. By providing a solid foundation in the fundamental principles of ASR and its applications, this section ensures that readers are well equipped to engage with the more complex ideas presented later.

The second section presents the media project developed for this study. It offers a detailed account of the hardware used, project limitations, structure, and fundamental systems. This practical component demonstrates the application of ASR technology in a videogame context, providing concrete examples of the challenges and opportunities in this field. The section concludes by addressing the challenges encountered during development and explaining how they were resolved, offering valuable insights into the practical implementation of voice recognition in games.

The third and final section focuses on analysis. It interprets the results of voice recognition control within the videogame industry and examines its limitations to address the study’s central question. By critically evaluating the outcomes of the media project and contextualizing them within the broader landscape of voice recognition technology, this section provides a comprehensive assessment of the potential for ASR in gaming. It concludes with a synthesis of the findings, leading to the final conclusion about the future of voice recognition in videogames.

This structure allows for a comprehensive exploration of the topic, moving from broad concepts to specific applications and analysis. It provides readers with a clear path through the research, from understanding the basics to examining practical implementations and drawing conclusions about the potential future of voice recognition in videogames. By organizing the thesis in this way, readers can follow the logical progression of ideas and gain a thorough understanding of both the theoretical and practical aspects of voice recognition in gaming.

State of the Art

This first section is crucial for understanding ASR. It provides an overview of the technology’s history, principles, and various applications, aiming to identify the strengths and weaknesses of this technology as it has been integrated into society. The focus then narrows to the objectives of ASR and its practical implementation in a media project.

Contextualization

The IT sector has witnessed a significant evolution in human-computer interaction over time. Initially, humans adapted to communicate with computers through hardware innovations like the mouse and ergonomic advancements such as the shift from text-based interfaces to graphical environments. However, this adaptation often excluded users with disabilities from fully interacting with digital devices.

Recently, there has been a paradigm shift towards machines adapting to human needs, largely driven by AI. AI’s capacity for autonomous learning and adaptation makes it well suited to meet industry demands, impressing current generations and likely continuing to captivate future ones.

It’s important to note that AI is not inherently linked to ASR. While some systems use machine learning to outperform statistical models, the choice of technology depends on the specific needs of the product and industry. Nevertheless, AI has brought ASR back into the spotlight, prompting society to reconsider its potential for deeper integration into daily life. Computers operate on a formal, binary language of 0s and 1s, lacking understanding of human language nuances, intentions or emotions. They rely solely on explicit, predefined instructions to carry out simple tasks. Despite these fundamental differences, human-machine communication remains essential across various fields and continues to evolve. The ultimate goal is to create more natural, intuitive, and effective interactions that can enhance human experiences in diverse contexts – from workplaces and educational settings to scientific research and recreational activities. These advancements are poised to transform the world around us, shaping our future interactions with technology. Moving forward, the focus is on developing systems that can better understand and respond to human communication in all its complexity, bridging the gap between human language and machine processing. This ongoing evolution in human-machine interaction promises to make technology more accessible, efficient, and responsive to human needs across all sectors of society.

Keywords

Musical Instruments and Sound Effects

A musical instrument is an extension of our means of communication, offering a multitude of ways to convey information and emotion, which vary significantly from country to country. For example, some cultures use mouth or finger percussion more prominently for communication. In Southern Africa, Khoisan and Bantu languages feature an extensive use of consonant phonemes and a common practice known as click languages. However, our focus here is particularly on the voice.

Voice

Voice is a unique living musical instrument, an integral part of the human body, whose sound production mechanisms remain challenging for most people to observe directly. The intention behind vocal expression is crucial for understanding the conveyed information. While emotion is primarily communicated through voice in many languages, its expression varies considerably based on cultural, educational, philosophical, and other societal factors which significantly influence communication styles.

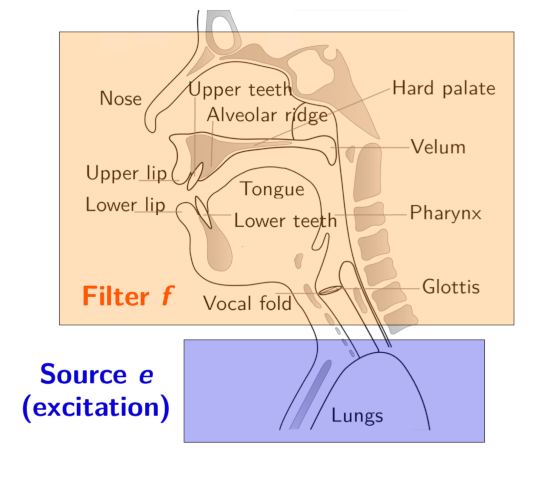

For the purposes of this study, we focus mainly on phonetic segmentation and speech rate, setting aside the complex emotional aspects of voice. The mechanics of speech production involve an initial airflow generated by the lungs, causing vibrations in the vocal cords. The resulting sounds, termed phonetics, are produced by air friction and amplified through resonant cavities such as the trachea, mouth, and pharynx. Understanding the fundamental aspects of voice production provides a crucial foundation for exploring how ASR systems interpret and process human speech. This knowledge is essential for developing more effective and nuanced voice control systems across various applications, including videogames. By focusing on the physical aspects of speech production, we can better appreciate the challenges and opportunities in creating responsive and accurate voice recognition technologies. This understanding is crucial for developing more effective and nuanced ASR systems, particularly in applications like videogames.

Phonetics

Phonetics, as a field, focuses on the segmented analysis of spoken sounds (phonemes) to examine their production, transmission, hearing, and evolution in human communication. This analysis contributes to the study of human language, a complex communication system that has evolved from conveying emotions for social harmony to describing concrete aspects of life for concise and objective communication.

Human Language

Human language is a complex communication system, and analyzing its intricacies is crucial for understanding ASR. The study of audio, vibration, noise, and surrounding sounds leads to the analysis of phonemes and syllables, which are the building blocks of language codes linked to human culture and history. Initially, communication focused on conveying emotions to maintain social harmony. Over time, language has evolved to describe concrete aspects of life, enabling more concise and objective communication. This evolution reflects the increasing complexity of human societies and the need for more precise information exchange.

Automatic Speech Recognition

ASR technology enables computers to convert spoken human language into plain text through a complex process consisting of evolving algorithms and language models. This section explores various ASR types, their core features, and the challenges they address.

Acoustic Pretreatment

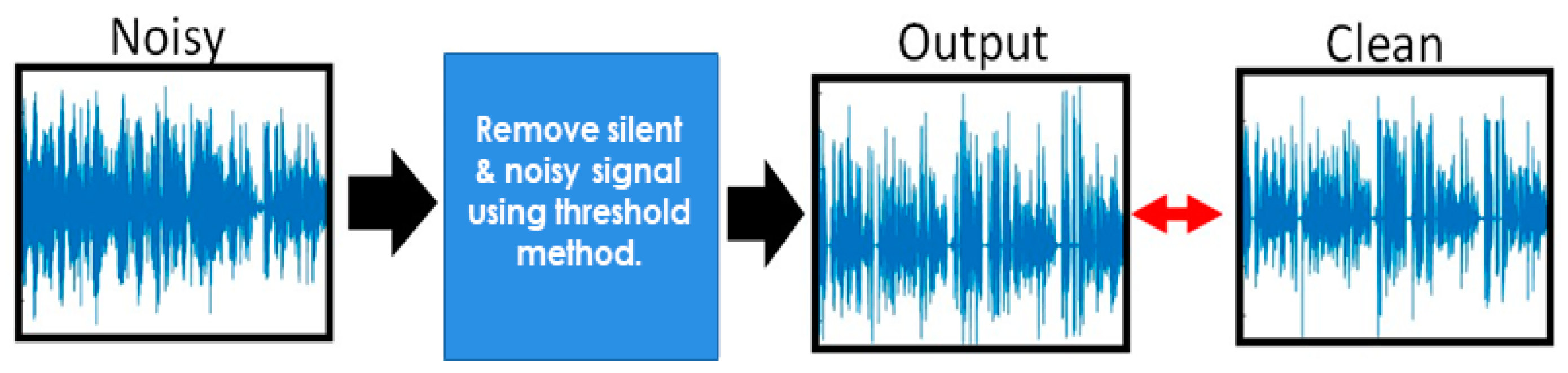

The process begins with acoustic pretreatment, capturing speech signals via microphones. These signals often include undesirable background noise.

Audio signals, electronic representations of sound waves, are measured in decibels, frequency, and amplitude. Acoustic pretreatment involves electronic manipulation to reduce noise, normalize volume, and remove interferences, isolating what’s needed for the algorithm search stage. The analog signal is then converted to digital data for deconstruction.

Algorithm Search

Algorithm search is the core of ASR technology, aiming to determine the best sequence of spoken words with the lowest possible transcription error rate. System performance varies depending on specialization, search method, language model, and vocabulary size restrictions. Various linguistic analysis processes and calculation techniques refine transcription accuracy.

Acoustic Model

An acoustic model represents the relationship between audio signals and phonemes or other linguistic units comprising speech. It’s trained using audio recordings and corresponding transcriptions, creating statistical representations of sounds to predict likely phonemes.

Language Model

A language model is a statistical representation of symbol distribution in natural language, predicting the next word in a sequence and forecasting likely word sequences. These models are formed by observing word sequences in text corpora, with each word appearing in the pronunciation dictionary.

Pronunciation Dictionary

The pronunciation dictionary contains word pronunciation details, including all words the ASR engine needs to recognize. It comprises records of words, some with multiple pronunciations, and is language-specific. The dictionary is manually built for the targeted language. In practice, ASR uses various algorithms, with the choice depending on specific needs. This comprehensive approach to ASR technology enables increasingly accurate and efficient speech recognition across diverse applications and languages.

Performance Evaluation

The performance of an ASR system is typically measured by the word error rate, which is the ratio of misclassified words to the total number of words tested. Current research aims to minimize recognition errors to zero in real time, regardless of vocabulary size, noise, speaker characteristics or accent.

The word error rate (WER) is calculated as:

$ “WER” = (I + E + S) / N $

where $S$ is the number of substitutions, $E$ the number of elisions, $I$ the number of insertions, and $N$ the number of words in the reference transcription.

Word Accuracy

Word accuracy (WAcc) is another measure used to evaluate the quality of ASR systems, defined as $%“WAcc” = 100 - %“WER”$. It’s important to note that accuracy can sometimes yield negative results. The WER measure is generally considered more valuable than WAcc, and for this reason, it’s more commonly used.

ASR History

The history of ASR spans several decades, marked by significant milestones.

-

In 1952, Bell Labs created Audrey, considered the first electronic voice-recognition device. It could identify digits 0 to 9 when pronounced separately.

-

A decade later, in 1962, William C. Dersch at IBM developed The Shoebox which not only identified the 10 digits but also recognized 16 English words related to mathematical operations.

Note. A demonstration at a 1961 press conference for newspaper, national magazine and trade publication reporters Shoebox’s small size was made possible by its advanced circuitry. It required only 31 transistors — fewer than two per recognized word. Earlier speech-recognition machines, by contrast, required as many as 200 transistors per word. Shoebox was also able to identify complete words, not just sounds or parts of words.

-

1971 saw a major advancement when the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) began work on Harpy, the first ASR system capable of understanding a vocabulary exceeding 1,000 words. Despite these advancements, ASR remained largely confined to specialized areas for many years.

-

Around the turn of the century, manufacturers began exploring ways to integrate this technology more broadly into their products. This expansion allowed ASR to find new applications across various industries and in everyday life.

-

A significant shift occurred in 1990 when Dragon Systems launched an ASR program aimed at the general public. Seven years later, the company introduced Dragon Naturally Speaking, the first recognition software capable of understanding complete sentences.

The 21st century brought rapid advancements. In 2008, Google launched an Internet search application utilizing ASR functionality. Three years later, in 2011, Apple introduced Siri on the iPhone 4S, marking a new era of virtual assistants in mobile devices.

“Initially perceived as a novelty, SIRI has demonstrated significant potential through recent examples, suggesting its evolution into a new form of human-machine interface. This technology is poised to become as integral as keyboards, screens, mice, and touch screens in our interactions with devices.” #cite(

The advent of the Internet and its vast and enthusiastic player base has led to the convergence of voice recognition technology with AI, resulting in more refined and specialized versions. In just half a century, voice recognition has developed to become a fundamental part of society, adapting to various industries and applications.

Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)

ASR systems rely on various technologies and algorithms, often in conjunction with AI. One such model is the GMM, which parametrically estimates the distribution of random variables by modeling them as the sum of several Gaussian distributions. In speech processing, GMMs are used to model the voice spectrum generation process, capturing the complex variability in voice signals and enabling effective modeling of the underlying structure of the voice spectrum.

Hidden Markov Model (HMM)

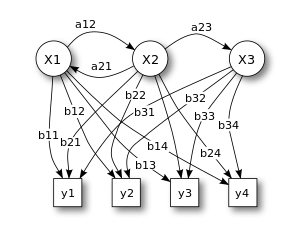

An HMM is based on the Markov chain model, a stochastic process that determines the probabilities of transitioning to a given state based on the current state. This fundamental property allows for predictions about future states without relying on previous states, even though the states themselves are unknown to the user.

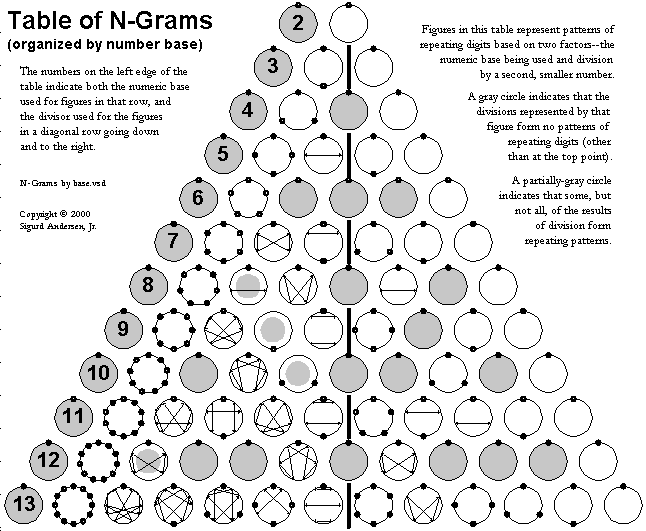

N-Gram Model

An N-Gram model is a probabilistic linguistic model based on a Markov chain of order N-1. It analyzes sequences of n adjacent elements in a given instruction to predict the likelihood of word or phoneme combinations in sentences and speech. This approach aims to improve the accuracy of language modeling and speech recognition systems.

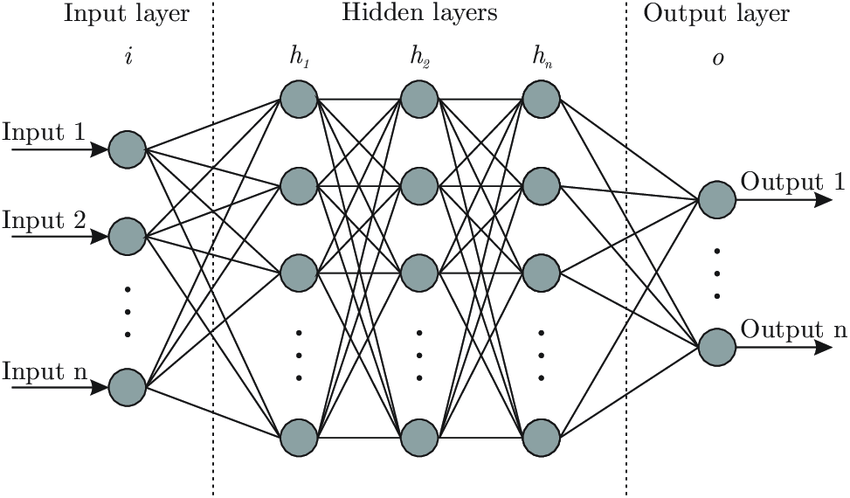

Neural Networks

Neural networks, primarily used for deep-learning algorithms, leverage data banks by mimicking the interconnectivity of the human brain through different layers of nodes. Each node consists of inputs, weights, a threshold, and an output. If the output value exceeds a given threshold, it activates the node, transmitting the data to the next layer of the network.

Note. This is the number of features your neural network uses to make its predictions. The input vector needs one input neuron per feature. For tabular data, this is the number of relevant features in your dataset. You want to carefully select these features and remove any that may contain patterns that won’t generalize beyond the training set (and cause overfitting).

Neural networks learn this mapping function through supervised learning, with adjustments based on the loss function using the gradient descent process. While neural networks tend to be more accurate than traditional language models and can handle larger datasets, this increased accuracy comes at a cost: they are often slower to train compared to traditional models, impacting overall performance.

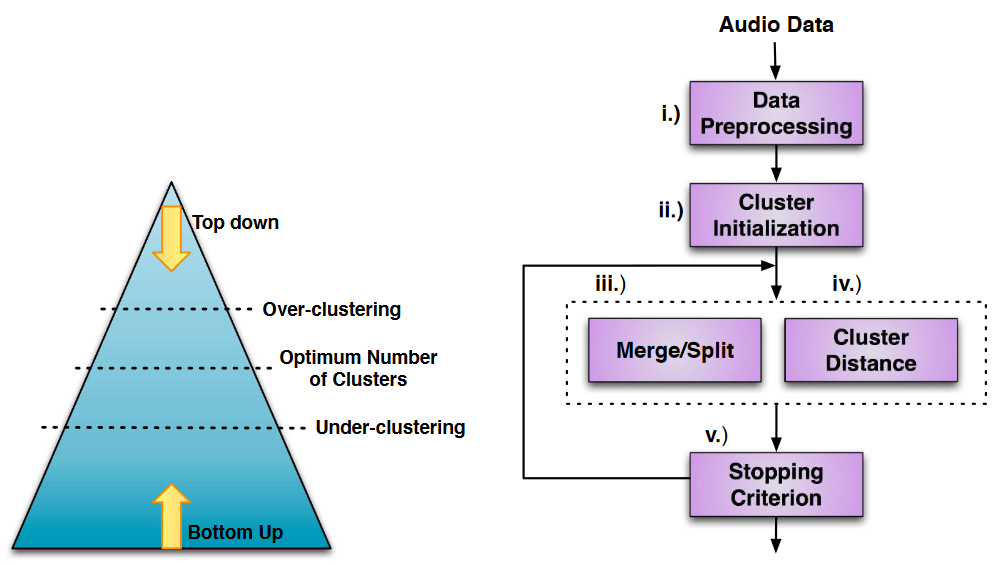

Speaker Diarization

Speaker Diarization enhances HMM efficiency by deconstructing audio data and identifying individual speakers, using either bottom-up or top-down clustering strategies.

Bottom-up algorithms separate all the audio content into a succession of small segments and then reassemble the parts which most closely resemble the speaker. In contrast, top-down algorithms start with a single segment containing all the data and iteratively separate them until they reach the same number of segments as there are speakers.

Note. (right) Alternative clustering schemas, (left) General speaker diarization architecture.

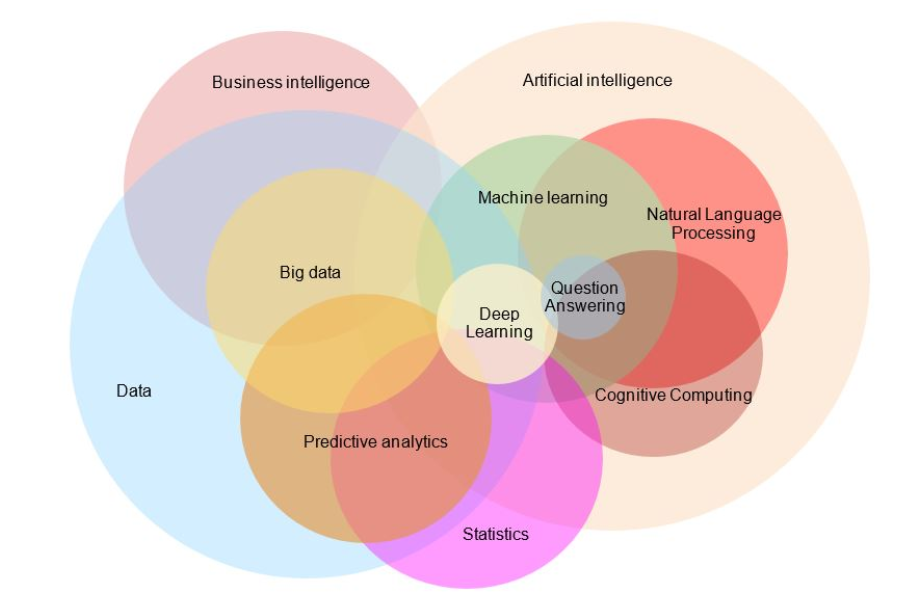

Natural Language Processing (NLP)

NLP is a multidisciplinary field which combines linguistics, computer science, and AI. It focuses on enabling machines to understand, interpret, and generate human language in a valuable way. NLP falls within the broader domains of AI and machine learning, allowing computers to process natural language inputs and produce text-based outputs.

Note. You can see NLP in red.

ASR Applications

ASR technology has found widespread applications across various industries, continuously expanding its integration.

Virtual assistants in smartphones and smart speakers use ASR to enable voice commands and provide user assistance.

In terms of accessibility, ASR helps individuals with disabilities by enabling voice control over devices and converting speech to text for those who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Transcription services utilize ASR to automatically document meetings, lectures, and interviews, saving time and effort.

In customer service, call centers employ ASR to route calls and handle inquiries through interactive voice response systems.

Aerospace

In aerospace, ASR technology was used on the Mars Polar Lander in 1999 to record frequency spectra for subsequent analysis of information and tones on the Red Planet. @CNN1999Lander

Automatic Translation

Automatic translation aims to facilitate understanding between people regardless of language barriers, becoming essential in today’s globalized world for political, commercial, sporting, and personal interactions.

Hands-Free Computing

Hands-free computing enables interaction without manual input or traditional digital peripherals, relying on voice commands to control user interfaces and execute instructions. This technology benefits both able-bodied and disabled users across various domains. The goal is to develop ASR systems capable of recognizing specific commands, verifying their accuracy, and transmitting instructions to the target system using voice as the sole input method.

For able-bodied users, this technology can streamline and expedite tasks in various professional settings. Engineers can manage operations more efficiently, while pilots in fighter jets #cite(

isually impaired individuals have particularly benefited from computers adapted to their needs. This area of study focuses on developing solutions that rely solely on voice input for issuing instructions. In the medical field, this technology has enabled surgeons to take notes during operations and has improved patient monitoring and pathology research. [Source nes]

Beyond these applications, these technologies show promise as diagnostic tools for the early detection of speech pathologies associated with health conditions such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. Additionally, they serve as assistive technologies aimed at enhancing the quality of daily life for many individuals. #cite(

Speech-to-Text

Transcription work is extremely arduous due to the vast amount of video content posted online. For example, in 2023, YouTube recorded an average of 500 hours of new content uploaded every minute. While communities strive to transcribe their content into different languages, the sheer volume necessitates the use of automatic transcription systems to meet this demand effectively.#cite(

Virtual Assistant

Virtual assistants have become one of the most widely adopted technologies in our society. Found primarily in smartphones, they optimize and revolutionize administrative tasks. Users can manage their calendars, send messages to contacts, and perform various other functions with just a few spoken words, eliminating the need to physically interact with their devices. Virtual assistants like Siri, Cortana or Bixby may well replace traditional methods of device interaction in the future.

Videogames

The videogame industry has integrated ASR technology, leveraging the diversity of genres and game mechanics to create innovative experiences. Speech-to-text functionality enables players to control game mechanics or communicate textually without interrupting their avatar’s actions. Conversely, text-to-speech and speech synthesis enhance immersion and storytelling, creating virtual worlds that foster reflection and innovation through varied environments. This technology’s application in gaming often borders on science fiction, providing an ideal platform for designing media projects that create tailored environments for specific challenges. By seamlessly incorporating voice commands and synthesized speech, video games are pushing the boundaries of interactive storytelling and player engagement, opening up new possibilities for immersive and accessible gameplay experiences.

Videogame Mechanics

Media projects have been created using ASR technology integrated with videogame mechanics. Whether as a central or secondary device in gameplay, its use varies widely across different practices in the industry.

Hey You, Pikachu!

Hey You, Pikachu! is a 1998 Nintendo 64 game developed by Ambrella Studio, utilizing voice recognition technology. Players communicate with Pikachu using voice commands to complete quests assigned by the professor, testing the “PokéHelper” device. The game uses the Voice Recognition Unit, an audio peripheral capable of detecting 256 words in Japanese or English.

Life Line: Voice Action Adventure

Lifeline, a 2003 PlayStation 2 survival horror action-adventure game developed by Sony Interactive Entertainment and Konami, features a unique voice-activated user interface to control the character Rio. Players dictate her actions as the plot unfolds. The game received positive reviews for its originality, with Game Informer rating it 8.75/10 and IGN 6.8/10.

By holding down the circle button, talking, and releasing the button when you’re done, Rio will respond by performing the action requested (if she understands), proclaiming you to be a total tool (if you said something that offended her), or telling you that she didn’t hear you. As long as she understands what you’re saying, it works surprisingly well, despite some occasional, probably hardware-related, problems. Also, the game has some built-in help to make sure the you and the waitress are on the same page. GameInformer August 19, 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

In Verbis Virtus

In Verbis Virtus, a 2014 adventure game by Italian studio Indomitus Games, offers a first-person experience where players cast spells by vocally reciting incantations. The game blends action and puzzle elements in a fantasy setting, using the CMU Sphinx API for voice recognition.

Note: Screenshot lorsque que le joueur effectuer le sort premier sort du jeux aprés avoir prononcer correctement le sort souhaité afin de résoudre l’énigme de la pièce.

Reception on Steam, the online distribution platform, has been generally positive for In Verbis Virtus, although some negative reviews highlight performance issues in action detection. Critical sites have been more favorable, with multiplayer.it awarding it 8.0 out of 10, and gamers rating it an average of 9.4 out of 10.

The game’s main appeal lies in its innovative spell-casting system, where players recite magic formulas directly into their microphones. This concept is so captivating that merely reading the game’s description evokes images of a Skyrim-esque scenario, with players shouting “FIRE BALL!” to incinerate hordes of monsters, akin to an armed and enraged version of Harry Potter.

Minecraft

Note: exemple de rendu, avec l’association du mod bubble chat afin de facilité grandement la communication en sein du jeu vidéo Minecraft.

Minecraft, the world’s best-selling game, has seen a resurgence in automatic speech transcription through mods like Microphone Text Input via the VOSK Offline Speech Recognition API. These mods enable text chat communication without interrupting avatar control, enhancing realism and immersion. Speech-to-text technology allows players to focus on the game’s atmosphere while maintaining seamless communication.

Text-to-Speech

Skyrim

Text-to-speech and speech synthesis represent significant advancements in gaming, particularly exemplified by modifications to games like Skyrim. These technologies create a seamless link between ASR and AI, enabling non-player characters to hear and respond logically to player input. This development marks an impressive yet unsettling evolution in AI technology, promising to make videogames substantially more immersive in the coming years. Numerous media projects, games, and mods in older games #cite(

Challenges

Despite its rapid advancement, ASR continues to face significant challenges in addressing the complexities of human linguistic communication and the acoustic environment. The key difficulties include:

Accents and Pronunciations Managing the diversity of speaker accents and pronunciations remains a challenge. Models must be trained on speech data which encompasses a wide variety of accents to improve accuracy.

Background Noise Background noise, muffled speech, and poor audio quality can severely impact transcription accuracy. Techniques such as speech enhancement are employed to mitigate these issues.

Multiple Languages Supporting ASR for the thousands of languages worldwide, each with its own unique sounds, grammar, and scripts, is a monumental task. While techniques like transfer learning and multiple language models are beneficial, collecting sufficient data to train models for each language remains a challenge.

Specialized Vocabulary Various use cases require different lexical fields, especially in domains like medical dictation, which involves highly specialized terminology which generic models struggle to handle. Customized models must be trained using domain-specific data to effectively manage these specialized vocabularies.

Future Advancement

ASR technology has made significant strides in various applications, including videogames. Voice control in gaming is still evolving, with its potential for universal adoption dependent on overcoming several challenges. Currently, AI and ASR have advanced to the point where simple voice commands can control smart home devices or assist individuals with disabilities, as exemplified by Stephen Hawking’s use of technology in his groundbreaking physics work.

Various industries are eager to adopt and integrate these technologies to enhance accessibility and functionality. In the videogame industry, voice control remains one of the less explored areas due to development challenges and limitations. However, this presents an opportunity for innovation and research. As industry professionals suggest, “that’s why it’s the right time to experiment with it in art and games”. #cite(

Voice Recognition APIs

While custom voice coding and data collection software development are always an option, several ready-to-use solutions are already available. Commercial APIs offer ASR algorithms, though they may not be easily customizable. User-friendly APIs for collecting speech data and developing tailored software include Google Cloud’s Speech-to-Text model, IBM Watson’s Speech to Text, and Nuance’s ASR. Open-source ASR systems are also available online, enabling community exploration and deeper understanding of the technology.

Some notable tools include:

Sphinx 3

An evolution from Sphinx 2, it uses a continuous HMM representation for high-accuracy, non-real-time recognition. Recent advancements have made it “near-real-time”, though not yet suitable for interactive applications.

Whisper An ASR system trained on over 680,000 hours of supervised multi-language, multi-task data from the Internet. Its extensive dataset enhances robustness against accents, background noise, and specialized language, facilitating multi-language transcription and translation into English.

Microsoft Speech API (SAPI) Developed for Windows Vista, SAPI it uses the N-Gram model for voice commands to control computers, enabling document completion, email sending, command shortcut improvement, and web browsing. Various fields recognize ASR’s potential, aiming to integrate it further to enhance processes, improve performance, and streamline operations. In videogames, the possibility of integrating speech-to-text technology could pave the way for new genres with unique gameplay mechanics and player experiences, though the complexity of human speech adds another layer of challenge to this exploration.

Limitations of Media Project

Speech-to-Text Responsiveness

To maintain a swift reaction time within the media project, we’ve eliminated all algorithm models requiring remote connections to AI for speech interpretation. This decision prioritizes interactivity and speed of interaction between the player and the media project, minimizing delays between instructions and maintaining playability comparable to that of a standard mechanical keyboard.

Language

French has been selected as the language for the media project, given its location in the French-speaking region of Switzerland. This choice optimizes speaker comprehension within the project, as ASR often struggles with English spoken with a strong French accent.

To maximize control reactivity for each adapted gameplay, a word limit has been imposed on instructions. To ensure concise and clear understanding when analyzing transcribed speeches, negations are disregarded. Voice intonation is also ignored, as it falls outside the scope of this thesis, and the selected API doesn’t provide this information in its basic form.

Although emotion is intrinsically linked to our words and voice, altering it uniquely for each individual, this aspect isn’t considered in this media project. The focus remains on the precision of human language and word analysis.

Statistical Model & Machine Learning

This area demands the most in-depth expertise. To produce a feasible and autonomous media project, AI-related aspects are limited mainly to developing a videogame environment which incorporates voice recognition. Given that a Bachelor’s degree is the prerequisite starting point in AI expertise, machine learning and deep learning are excluded from the outset. A statistical model has been chosen for this thesis, though exploring the issue further with AI use would be intriguing in future stages. #cite(

Complexity Level

Several characteristics in a speaker’s words can be analyzed. To progress step-by-step and delve deeper into managing various analyzable data to alter the control of this media project, we’ve established the following levels:

Simple Instruction

A simple instruction aims to prove the system’s ability to account for the speaker’s speech, interpret it, and execute commands. For example: “the cube jumps”. We select an entity and give it a basic action.

Intermediate Instruction

An intermediate instruction aims to select an entity precisely and give a complex instruction, generally recommending arguments to contextualize the instruction and goal. For example: “the large red cube moves forward 35 meters”. We select an entity with certain characteristics and give it an action with a precise distance, detecting the number (35) and its type (meter) to create an argument.

With these limitations in place, we can now design a media project. Developing a voice-controlled videogame allows us to explore the extent to which this technology can be developed and implemented in various test environments.

Media Project

This chapter focuses on the practical aspect of the media project, developing a tool to address the question at the heart of the thesis. It then describes tests demonstrating the potential future of ASR in this media type.

All the information analyzed in the previous chapters is part of an empirical approach to set up a development environment for producing a mini-games type videogame. An ASR was used to collect as much data as possible, enabling visualization and interpretation to draw conclusions about the final results.

General Description

This media project aims to employ the player’s voice as the sole command input. Players solve various tests to control and correctly respond to problems at different complexity levels of voice control. The media project explores whether certain videogames could be adapted to voice or if a new voice-based genre could emerge in the videogame industry.

Given the vast array of videogame genres, the project’s scope has been limited to ensure feasibility. A mini-game format was chosen as the most judicious approach to test various mechanics. To maximize achievements within the thesis time constraints, certain limitations have been imposed. This focused approach allows for a comprehensive exploration of voice control mechanics across different game scenarios while maintaining a manageable project scope.

Exploitation of Mini-Games

Mini-games serve as a powerful tool for creating fast-paced environments suitable for data collection. They highlight aspects observable in certain genres, offering a unique perspective of voice control in videogames. The focus is on designing classic genre mechanics for observation.

Action games require real-time instructions and primarily test the player’s skill and reflexes. The Mario Party series exemplifies this, combining board games with mini-games where players cooperate or compete to become the superstar.

Management games allow players to act without time pressure, typically involving the oversight and improvement of an organization in a specific area. Oxygen Not Included demonstrates this, challenging players to utilize available resources to produce oxygen for crew survival while managing various elements such as gases, liquids, temperature, disease, stress, radioactivity, food, expansion, science, waste management, tidiness, agriculture, and electricity.

Strategy games generally involve controlling units or buildings. Age of Empire II requires players to produce combat units and defensive structures while continuously gathering strategic resources to dominate enemies and ensure their civilization’s survival. Into the Breach offers another example, set in a post-apocalyptic universe where humanity faces giant insect-like kaijus. The objective is to protect civilian buildings and defense robots to survive as long as possible and potentially eliminate the threat.

Hardware Used

Computer

• CPU: AMD Ryzen 7 6800H With Radeon Graphic @3.2 GHz • GPUs: Nvidia GeForce RTX 3070 Ti Laptop & AMD Radeon(TM) Graphic • RAM: 16 GB @4,800 MHz • OS: Windows 11x64 architecture

Device Input Sound

• Microphone Array (Realtek(R) Audio) Format: 2 channels, 16 bit, 48,000 Hz (DVD Audio) • Trust Microphone

Software Used

• Game engine: Unity 2022.3.24f1 • Language: C# • IDE: Visual Studio 2022 • Text processing: Visual Studio Code • Office software: LibreOffice • Editing: Typst

Test Protocol

The test protocols for this thesis were implemented during a special event held at the University of Fribourg from 22 to 28 July 2024. This period was chosen to maximize participation across all age groups and collect diverse data. The Swiss Game Academy, a non-profit association, hosted the event, providing education for participants interested in game creation or those looking to enhance their skills in a team setting.

A dedicated team of coaches provided support throughout the event, assisting players in realizing their goals and ensuring that all media projects maintained a consistent level of playability. This support system helped create a level playing field for participants, regardless of their prior experience with voice-controlled gaming. The testing process was carefully organized into distinct sections, each tailored to the specific requirements of individual mini-games. This approach allowed for a thorough evaluation of voice control mechanics across different game genres and styles, from fast-paced action games to more strategic experiences.

Each mini-game underwent a specialized testing procedure designed to assess its unique features and challenges related to voice control implementation. This structured methodology enabled testers to focus on particular aspects of each game, providing valuable insights into the effectiveness and user experience of voice commands in various gaming contexts. For a comprehensive understanding of the testing environment and procedures employed during the event, including detailed descriptions of each mini-game’s testing protocol and data collection methods, please refer to the subsequent sections of this chapter.

Experiment Environment

In recent years, the videogame population has evolved in terms of where they gather to play. Initially confined to arcades, gaming has since invaded homes and is now accessible from various devices including smartphones, portable consoles, and laptops. The choice of location for voice-controlled gaming significantly impacts data capture, particularly affecting ASR performance. Six specific environments were tested to evaluate the effectiveness of voice control in different settings.

• F1 : Written speech • F2 : Spontaneous speech • F3 : Written speech with background noise • F4 : Spontaneous speech with background noise • F5 : Written speech with simultaneous speakers • F6 : Spontaneous speech with simultaneous speakers

To ensure smooth testing, players were familiarized with the necessary voice commands, equipping them with the tools to conduct the test under appropriate circumstances. This preparation was crucial for accurate data collection and fair evaluation of the voice control system across different mini-games.

The testing protocol focused on three specific scenarios: F1, F3, and F6, each simulating different real-life gaming environments. These scenarios were randomly assigned to players, providing a diverse range of testing conditions that reflected various potential use cases for voice-controlled gaming.

The testing setup was carefully designed to maintain consistency and control. Each test session involved two people:

-

A moderator equipped with loudspeakers to simulate one of the three randomly chosen scenarios (F1, F3 or F6). This allowed for controlled introduction of environmental factors that might affect voice recognition performance.

-

A player, provided with a computer and microphone, tasked with completing all mini-games and tests using voice commands.

This controlled environment made it possible to observe how different background conditions affected the performance of voice controls in various game types. By randomizing the scenarios for each player, the study aimed to gather comprehensive data on the effectiveness of voice control across a range of realistic gaming situations.

The setup enabled close observation of player interactions with the voice control system, allowing for the identification of strengths and weaknesses in different environmental contexts. This approach provided valuable insights into the practical applications and limitations of voice control in gaming, contributing to the development of more robust and versatile voice recognition systems for future game designs.

Experiment Procedure

This section details each stage of the experiment as it unfolded, along with the various roles involved. A moderator was responsible for overseeing each test, setting up all installations and events, and randomly initiating real-world situations using loudspeakers. The other participant in the test, the player, engaged in a mini-game to completion, allowing for data collection. The objective was to conduct a series of mini-games to evaluate player performance in managing instructions within a virtual environment using only the voice as a means of communication.

Basic Tests

In this initial phase, the tests aimed to introduce and assess the fundamentals of voice control. They evaluated the players’ adaptability and responsiveness, enabling them to achieve objectives across various test environments.

Hello World: In Hello World, players needed to say just one word to proceed to the next test, which served as an excellent starting point to observe differences in response speed.

What Shape: In What Shape, players had to verbally identify the largest of three 3D shapes—Capsule, Cube, Sphere—three times to complete the test.

What Color: In What Color, players were required to verbally state the colors displayed on a chart three times to finish the test.

Intermediate Tests

Building upon the basic tests, the next phase increased complexity by combining different functionalities. It challenged the player with new environmental situations linked to classic genre mechanics such as action, strategy, management, and adventure.

Door: In Door, players had to loudly pronounce written phrases to open each of the five doors blocking their progress.

Jump: In Jump, players were required to hold out as long as possible within a set boundary to avoid approaching obstacles with a single action.

Movement Entity: In Movement Entity, players were positioned among four equidistant colored entities and had to move closer to the indicated color.

Movement Space: In Movement Space, players were placed in an open area where they used multiple movement commands to reach the endpoint in the shortest time.

Advanced Tests

In the final phase, the tests further elaborated on the basics established in the earlier phases. The advanced tests introduced more intricate mechanics to increase complexity and proposed new challenges to assess a player’s ability to perform under pressure.

*Town Center*: The user initially has one villager and a forum. They can collect 3 different resources and must obtain a total of 500 wood to pass this test.

Quantitative Measurement

Upon completion of the different phases, quantitative measurements from all tests were automatically exported to a CSV file for analysis. The values were color-coded to differentiate significant results according to control peripherals: blue for microphone (M) and red for keyboard (K).

Measured data included:

• Peripherals used (keyboard or microphone) • Time taken to reach test objective • Number of misunderstood instructions • Total inactivity time

For each instruction, the following data was collected: • Difficulty level (beginner, intermediate, advanced) • Time elapsed since the last instruction • Instruction completion time • Instruction type (movement, action)

The data were processed to compare certain values, including mean, variance, and median. A statistical test was conducted using a null hypothesis, which posits that any difference in values between microphone and keyboard use isn’t merely coincidental.

The primary focus of the study was to compare differences between microphone and keyboard input. While it was expected that keyboard input would yield significantly different values due to its integration in computing and gaming, it served as a crucial benchmark. This comparison aimed to identify mechanisms likely to reduce this difference in the videogame field and uncover potentially unexploited genres suitable for speech input.

Implementation Process

Results

In most studies on voice control, standard peripherals consistently demonstrate superior performance and responsiveness. However, it’s essential to examine how the differences between various peripherals, particularly in relation to videogame genres, may affect performance. Is a significant convergence between the different input methods possible?

Technical Implementation

This chapter delves into the intricate design process behind the videogame developed for the experimentation phase. It outlines the core design elements of the media project, detailing the algorithms employed and the comprehensive tasks undertaken to bring the game to fruition.

SOA or Keyboard Killer

Once speech-to-text functionality is operational, the working environment within the game engine is ready to design the main algorithm, code-named “SOA” (Selection Order, Argument) or “keyboard killer”. To implement an algorithm that segments the player’s transcribed speech and identifies the desired action, it’s crucial to break down the various components.

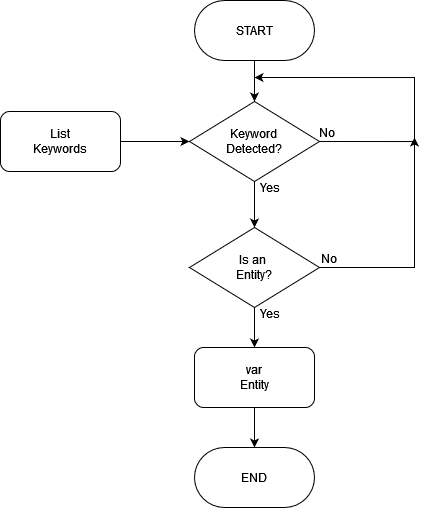

Identifying Instructions

Executing actions through verbs can be relatively challenging due to two major issues. First, the multitude of verbs that can convey the same action, as individuals often phrase requests differently, necessitating consideration of various formulations. Second, there is the complexity of conjugation. In the French language, verbs are used according to their tense (indicative, imperative, subjunctive, conditional) and are conjugated based on the subject. This significantly increases the number of different forms for a single verb.

To address this challenge, the range was simplified and all derivatives were converted into their lemma form, which streamlines the process. In linguistics, a lemma is an autonomous unit that constitutes the lexicon of a language, often referred to as the canonical form of a word. This reference form doesn’t include inflectional markings, allowing different morphological forms of a word to be grouped under a single term. The infinitive form served as the verb form, while the masculine singular form was used for adjectives and common nouns.

Note. Is the process of grouping together the inflected forms of a word so they can be analysed as a single item, identified by the word’s lemma, or dictionary form.

Selection

The first step in entity selection involved recognizing that proper nouns pose challenges for ASR; common nouns are far more preferable. For instance, to call a dog, one can simply say “dog”. While this works well, distinguishing between multiple dogs requires additional identifiers, such as color, breed, size or gender. To enhance the system’s complexity, entities must possess specific features that a player can select based on these differences.

Common nouns were indexed—words that identify entities capable of performing actions or instructions (e.g., cube, sphere, player)—to retrieve them from a list. Additionally, a table of adjectives (e.g., small, medium, large, red, blue, green) was used to identify, isolate, and select specific entities or groups from a diverse range.

Argument

An action must perform a specific task, but the arguments provided to execute the action can vary widely. For example, entity A may move toward the red square, toward entity B or 10 meters in a specified direction.

Therefore, arguments must be versatile to adapt to the different parameters of an action. An argument can take the form of “where” (direction, angle, space, entity), “what” (subject, object) or “when” (duration, date).

Entity Component System (ECS)

With the previous components established, entities can be selected, and instructions and arguments can be detected. The next step was to design how the actions and instructions defined by the player are executed. To finalize the mechanics of this media project, an ECS architecture was chosen.

An entity is defined as an object within a system, primarily serving as a unique identifier that can be linked to various components related to a given action.

A component represents the characteristics of an entity regarding a specific aspect. It stores the data necessary for the action which the system manipulates.

A system processes the data in the relevant component(s) to complete the entity’s action. Together, these three elements form the core of the system, enabling it to fulfill the tasks required by the player.

The aim of this structure is to be data-oriented, but for the complexity of the project it will be object-oriented to simplify the development of the project media.

Now that the various mini-game instructions were functioning, we focused on how the gameplay loops, rules, and tests interact.

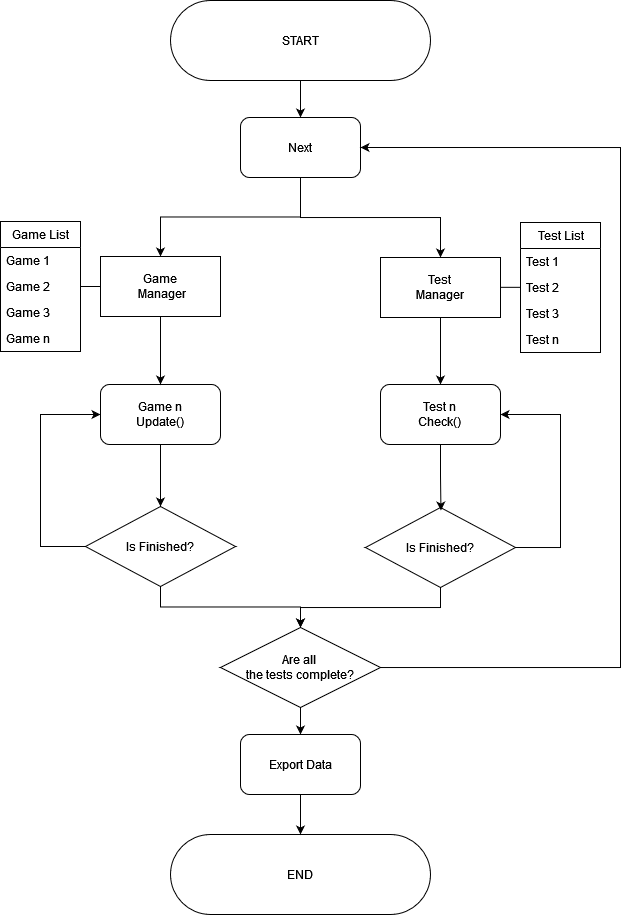

Gameplay Loops

With the control and action mechanics established, the next step was to implement systems that manage each test environment and the various gameplay loops to ensure smooth operation of the test protocol. Given that each gameplay and test had distinct mechanics and resolutions, it was crucial to identify operational similarities.

For each gameplay scenario, the moderator processed its actions in the main loop (Update), while for tests, he checked whether the test conditions had been met (Check). Inheritance was utilized to address this challenge efficiently.

In summary, the moderator was responsible for overseeing the various games and tests within the media project. The voice recognition API, along with the entity, action, and argument selection detection systems, as well as the ECS framework, were designed to interpret and resolve player actions. The final step involved integrating these different processes to create a functional media project.

These considerations conclude the core of the media project. A detailed discussion of the various systems designed within the ECS framework can be found in the appendix for further reference.

Results

In the results section, we analyze test outcomes from simplest to most complex, using statistical hypotheses to determine if the research data aligns with the issue at hand.

Levene’s test, a deductive statistic, assesses variance equality for a variable across two samples. If the p-value is below a significance level, there’s less than a 5% chance of being correct, and the null hypothesis is retained.

The Two-sided t-test examines differences between using a keyboard and a microphone regarding action time or exercise completion time. If the p-value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is retained.

If hypotheses are rejected, we observe differences in mean, median, and variance to determine if voice recognition in video games has a viable future and whether these exercises help identify its limits for more advanced uses.

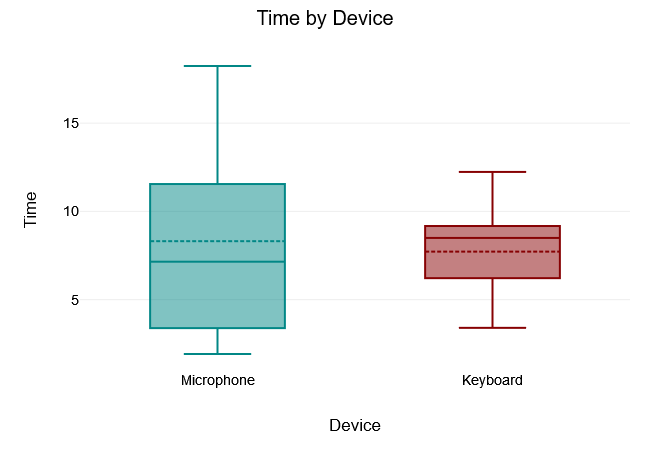

Hello Word

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.04$, which is below the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was rejected. Thus, there was no variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances not assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was not statistically significant, $t(12.32) = 0.27, p = .791$, 95% confidence interval [-4.14, 5.32]. Thus, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had higher values for the dependent variable Time $(“M” = 8.31, “SD” = 5.72)$ than the Keyboard group $(“M”= 7.72, “SD” = 2.98)$.

What Shape

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.118$, which is above the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore not significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was not rejected. Thus, there was variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was not statistically significant, $t(16) = 1.2, p = .248$, 95% confidence interval [-2.75, 9.93]. Thus, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had higher values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 8.89, “SD” = 7.49)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 5.3, “SD” = 4.33)$.

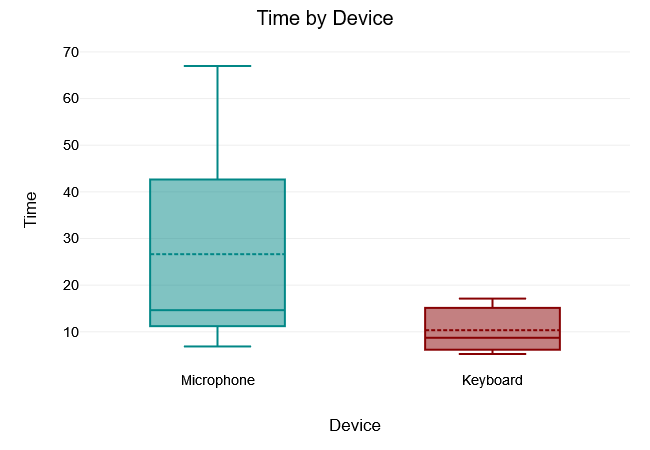

What Color

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$- of $.002$, which is below the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was rejected. Thus, there was no variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances not assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Clavier with respect to the dependent variable Time was statistically significant, $t(10.08) = 2.24, p = .049$, 95% confidence interval [0.1, 32.47]. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had higher values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 26.64, “SD” = 22.33)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 10.35, “SD” = 4.93)$.

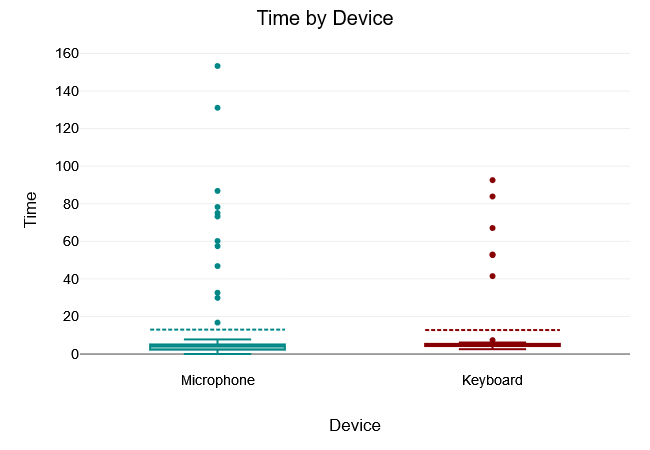

Jump

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.593$, which is above the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore not significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was not rejected. Thus, there was variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was not statistically significant, $t(126) = 0.04, p = .965$, 95% confidence interval [-9.36, 9.78]. Thus, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had higher values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 13, “SD” = 27.68)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 12.79, “SD” = 22.11)$.

Movement Entity

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.317$, which is above the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore not significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was not rejected. Thus, there was variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was not statistically significant, $t(33) = -1.16, p = .254$, 95% confidence interval [-54.66, 14.97]. Thus, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had lower values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 33.59, “SD” = 39.41)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 53.44, “SD” = 44.93)$.

Movement Space

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.224$, which is above the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore not significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was not rejected. Thus, there was variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was not statistically significant, $t(61) = -1.34, p = .184$, 95% confidence interval [-11.93, 2.34]. Thus, the null hypothesis was not rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had lower values for the dependent variable Time (M = 12.25, SD = 10.96) than the Keyboard group (M = 17.04, SD = 16.64).

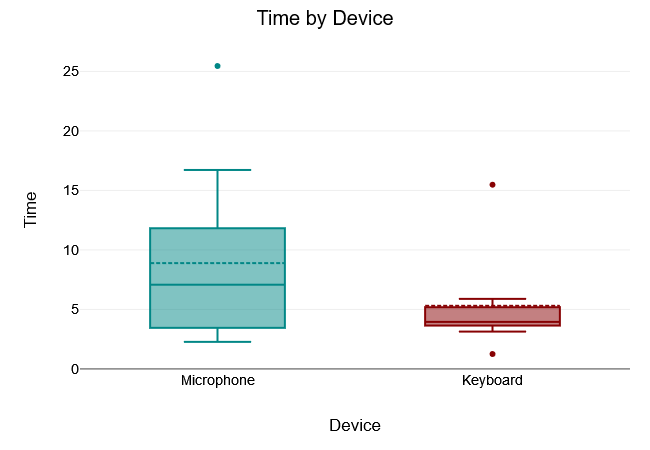

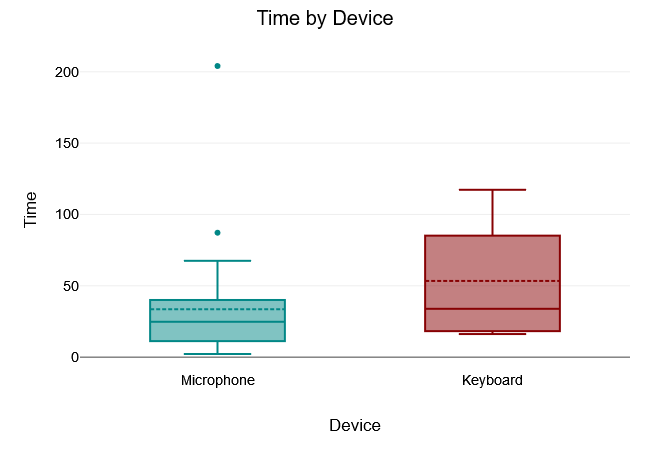

Door

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $<.001$, which is below the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was rejected. Thus, there was no variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances not assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was statistically significant, $t(6.11) = -4.98, p = .002$, 95% confidence interval [-100.65, -34.48]. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected.

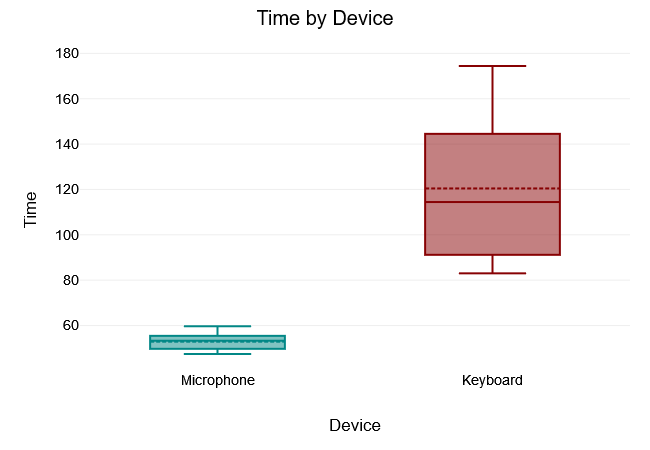

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had lower values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 52.9, “SD” = 4.09)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 120.47, “SD” = 35.74)$.

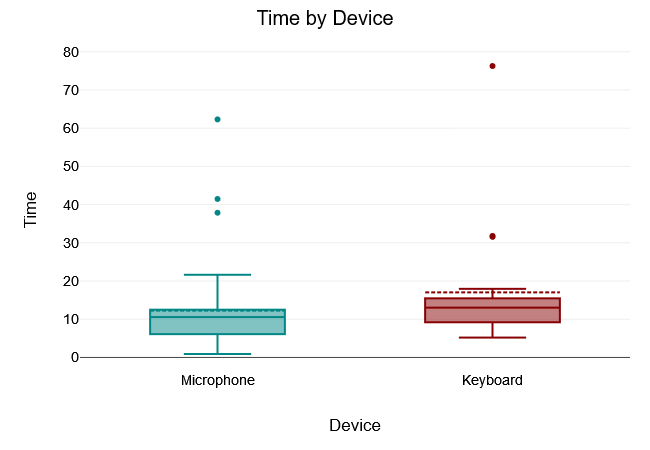

Town Center

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.006$, which is below the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was rejected. Thus, there was no variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances not assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Keyboard with respect to the dependent variable Time was statistically significant, $t(155.37) = -2.71, p = .007$, 95% confidence interval [-15.32, -2.38]. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had lower values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 13.91, “SD” = 17.98)$ than the Keyboard group $(M = 22.76, “SD” = 32.25)$.

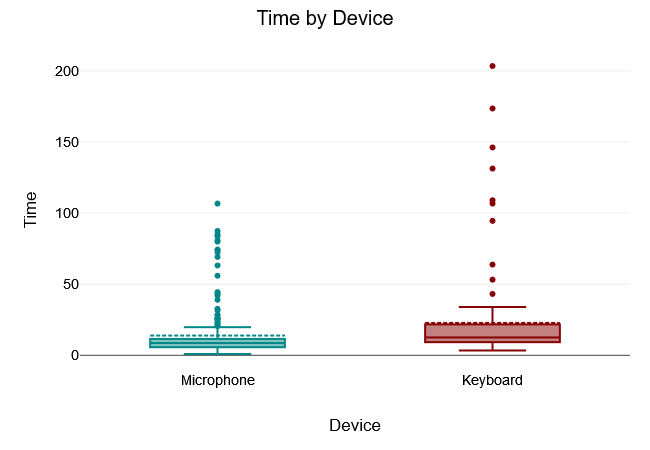

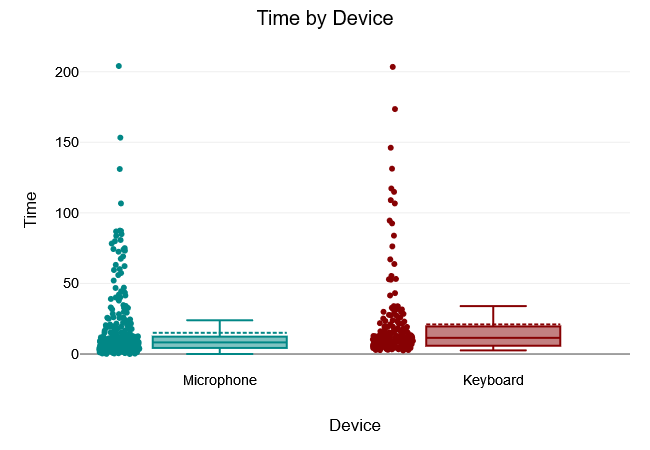

All Order

The Levene test of equality of variance yielded a $“p-value”$ of $.026$, which is below the 5% significance level. The Levene test was therefore significant and the null hypothesis that all variances of the groups are equal was rejected. Thus, there was no variance equality in the samples.

A two tailed t-test for independent samples (equal variances not assumed) showed that the difference between Microphone and Clavier with respect to the dependent variable Time was statistically significant, $t(293.02) = -2.35, p = .019$, 95% confidence interval [-10.98, -0.94]. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The results of the descriptive statistics showed that the Microphone group had lower values for the dependent variable Time $(M = 15.03, “SD” = 22.83)$ than the Clavier group $(M = 20.98, “SD” = 30.25)$.

Overall, the analysis highlights differences in performance between using a keyboard and a microphone for time-sensitive tasks. While keyboards tend to be faster for simple tasks like typing or saying a single word, microphones prove more advantageous for complex inputs such as complete sentences. This suggests that while keyboards are efficient for straightforward commands, voice recognition may offer benefits for more intricate interactions.

Discussions

In summary, I encountered several challenges during development. Firstly, the test setup wasn’t entirely resistant to user manipulation. At the Swiss Game Academy, players intentionally deviated from the intended path to uncover errors or test the voice recognition system’s transcription capabilities, which led to issues that significantly hindered user progress and complicated data collection.

Notwithstanding the above, voice recognition technology still requires further development for effective use in video games. While my project was successful on its own scale, the results it yielded are insufficient to define core game mechanics. More specialization is needed to create a truly unique product.

That said, I’m confident that the future of voice recognition in video games is promising. Statistics clearly show a difference in efficiency between using a keyboard and a microphone for basic tasks. But for lack of time, I wasn’t able to explore design methods and strategies that could significantly enhance action speed. These might include voice shortcuts or adapted user interfaces, similar to how keyboard shortcuts improve efficiency. As research and use of voice recognition deepen, voice shortcuts may become more prevalent.

The video game industry will undoubtedly create experiences that transform our relationship with voice recognition, deepening engagement and reaching new audiences, including those with disabilities. My personal goal is to develop a comprehensive game that fully integrates voice recognition transcription through one or more mechanics, offering a unique and accessible experience.

Glossary

Longitudinal Wave A disturbance of a medium that propagates in the same direction as the wave itself, contrasting with transverse waves where the disturbance occurs perpendicular to the direction of propagation.

Application Programming Interface (API) A communication protocol between different software components, defining a set of functions that allow applications to access specific features or data of an operating system, application or other service.

Software Development Kit A comprehensive set of tools, libraries, documentation, code samples, and guides enabling developers to create software applications on a specific platform. It typically includes a compiler, debugger, and often a software framework to streamline development.

Automatic Speech Recognition The process of converting spoken language into written text. This complex task involves capturing sound frequencies via a microphone, analyzing them, and translating them into machine-readable text. The challenge lies in interpreting the nuances of human speech, including context, tone, implicit expressions, sarcasm or humor, which often rely on non-verbal cues.

Statistical Model A mathematical representation of real-world phenomena, designed to simplify complex processes and make explicit hypotheses about the subject under study. Its primary purpose is to facilitate mathematical analysis and produce solutions that closely approximate observed data.

Corpora Large and structured sets of texts used in linguistic analysis. Corpus linguistics, a branch of study closely tied to the development of computer systems and textual databases, focuses on analyzing these sets of texts. Corpora are instrumental in studying language norms, including structure and code.

Machine Learning A field of study focused on developing algorithms and statistical models that enable computer systems to improve their performance on a specific task through experience. It involves providing computers with data and information from real-world observations and interactions, allowing them to learn and refine their learning methodologies over time.

ludothèque

Games

Hey You, Pikachu (December 12, 1998), Ambrella, Nintendo, Nintendo 64

In verbis Vertus (April 3, 2015), Indomitus Games, Indomitus Games, PC

life Line Voice Action Adventure (January 30, 2003), Sony Computer Entertainment, Sony Computer Entertainment, PS2

Minecraft (November 18, 2011), Mojang Studios and Xbox Game Studios and 4J Studios, Mojang Studios (PC, Mobile) and Xbox Game Studios (Xbox 360, Xbox One et Windows Phone) and Sony Computer Entertainment (PS3, PS4 et PS Vita) and Nintendo (Wii U, New Nintendo 3DS et Nintendo Switch) and NetEase (China)

Space Station 13 (February 15, 2003), Originally Exadv1, now community based, PC

Age of empire II (September 27, 1999), Ensemble Studios, Microsoft and Konami, Microsoft Windows and MacOS and PlayStation 2

Oxygen not include (February, 2017), Klei Entertainment, Klei Entertainment, Windows and Linux and MacOS

Into the breach (27 février 2018), Subset Games, Subset Games Windows and Mac and Linux.

= Annex